Uncovering exisiting bottlenecks

Before writing a line of code, the team from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Nairobi (UoN) listened closely to the people who live and work in the rangelands. Through twenty focus group discussions and more than thirty interviews, pastoralists, disease reporters, veterinary officers, and community leaders identified the real gaps and barriers they face in reporting diseases and responding to outbreaks. Both herders and animal-health professionals pointed to the same bottlenecks: limited access to veterinary services, slow information flow, and unreliable communication channels for sharing disease information and receiving advice.

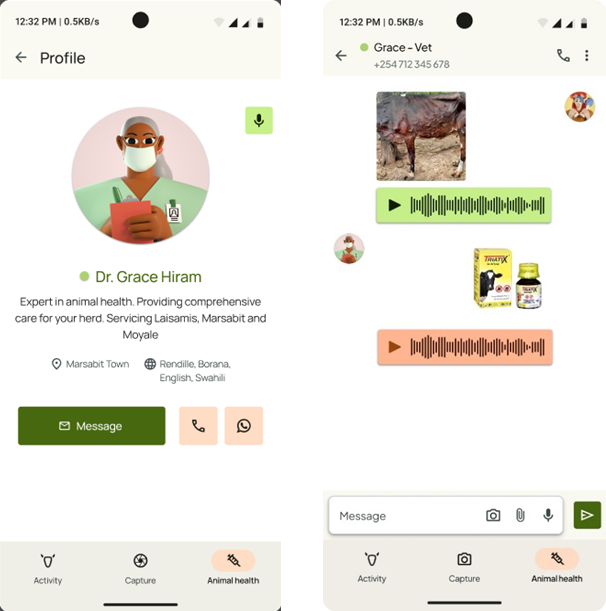

This shared understanding led PhD student Derrick Sentamu (UoN) to initiate the co-design of a veterinary app that connects herders with each other and with veterinary services—rather than simply pushing information to them. The app allows communication via voice messages, photos, and text so that herders can promptly report observed clinical syndromes. When livestock keepers share photos of sick animals, these appear on a digital disease map, generating geo-referenced reports that support timely responses and early warnings of new outbreaks. Field research showed clearly that a successful digital tool must work on basic smartphones, function in areas with poor connectivity, and require minimal mobile data. Importantly, the design must reflect communication practices already used by pastoralists, rather than those imagined by software developers in distant cities.

To complement this co-design process, PhD student Rufo Compagnone (DITSL) and colleagues emphasized the importance of digital inclusion as a foundation for participation. Through InfoRange, specially trained Volunteer Information Facilitators (VIFs) have been working with pastoralist communities in northern Kenya and Namibia to build smartphone literacy. This has enabled herders to document grazing and animal-health conditions through photos and share them within their networks.

Herders’ needs and interests integrated

The co-design discussions also revealed strong interest among pastoralists and veterinarians in having a dedicated space within the app to access practical animal-health and rangeland knowledge locally and offline. Such a digital community knowledge centre could host audio, photos, short videos, and practical guidance in local languages. It could become a repository where information on livestock and zoonotic disease management, prevention, treatment, and medicines can be easily accessed—even by users with limited literacy—through images, audio, and local-language content. Additional topics might include poisonous plants, seasonal grazing strategies, and drought preparedness. The interest expressed by communities highlights an exciting direction for future development.

One of the insights from this work is that pastoralists are not digitally inept nor technology-averse. In fact, they are already creative adopters of mobile solutions when these help them navigate uncertainty. They want to participate actively in shaping the solutions that affect their livelihoods. The co-design approach demonstrated how herders can become collaborators rather than merely beneficiaries. They identified what information matters most to them, how it should be shared (publicly or privately), and which functions a digital tool must have to be useful in their everyday lives.