What if knowledge about climate change could circulate more freely, from universities to the fields? What if local languages were not an obstacle, but a lever? This is the challenge embarked upon by the French-Kabiyè climate glossary, a linguistic tool designed to strengthen sustainable land management in rural communities in northern Togo as part of the Minodu project.

Why a glossary?

In every specialized field, technical vocabulary emerges: often complex, sometimes opaque. Climatology is no exception. While this vocabulary is essential for researchers, it becomes a barrier when it comes to communicating with local communities in sub-Saharan Africa, who are nevertheless on the front line of climate change.

Imagine: You are a student of agriculture at a university. In your studies, you have learned about the importance of climate change, the severe effects it will have on regional agriculture, and potential solutions that could greatly improve rural farmers’ ability to implement agricultural interventions. These are learnings that could directly impact your home community, so you want to share it with them. But you realize: you cannot find the words in your mother tongue to explain your learnings to the rest of your community! You have all the words crystal clear in your language of instruction, but you struggle to find the words in your mother tongue…is there even a word for climate change in Kabiyè?

Situations like the above scenario are more common than we think, and such situations were our main motivation in developing a technical glossary. A technical glossary is more than a dictionary; it translates scientific concepts into a targeted language adapted to the local context and specifies uses, nuances, and equivalents. In short, it bridges two worlds: that of academic knowledge and that of knowledge rooted in the land.

A tool rooted in the Minodu project

This glossary was created as part of the Minodu project, which promotes participatory scientific communication on climate and sustainable agriculture. Kabiyè, one of the most widely spoken languages in Togo, was the obvious choice: widely spoken in the Kara region, it is the everyday language of many agricultural producers.

But translating terms such as “climate resilience” or “weather hazard” is not straightforward. It requires more than a simple literal translation. It involves in-depth work with native speakers, listening to local representations of climate, and paying attention to oral and cultural forms of knowledge transmission. It begins with the observation that there is no single word in Kabiyè for “climate.” It continues with the recognition of the vast reservoir of climatological knowledge that is “rooted in the land” and the people who till it, which is endogenous, embodied, but unwritten, and difficult for the scientific community to see. This knowledge can only be used with a very respectful approach, which begins with establishing a common basis for communication.

A collaborative and rigorous method

The glossary was co-constructed in several stages:

- Selection of terms: a multidisciplinary team identified key terms from existing climatological glossaries and technical documents (particularly those from Togolese and international meteorological agencies).

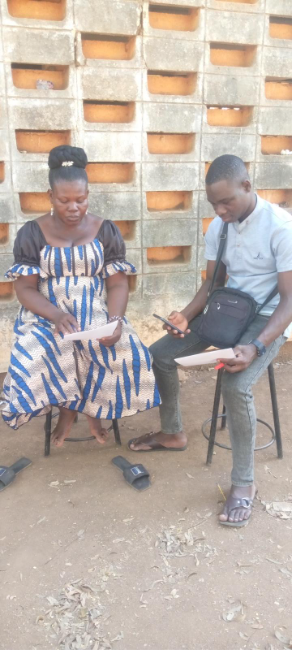

- Community collection: working sessions were held with resource persons from three villages in the Kara region, combining linguistic expertise and field knowledge. Questions ranged from the simple “how do you say climate?” to open-ended questions about the seasons or perceived climate change.

- Phonetic transcription: responses were carefully transcribed using the International Phonetic Alphabet, respecting the specificities of Kabiyè, with the support of the Kabiyè Academy at the University of Kara.

- Community validation: a workshop with a wider range of Kabiyè speakers provided an opportunity to collectively discuss terminology choices, adjust certain formulations, and enrich the glossary with dialectal variants and phrases used in context.

A living, vibrant, and accessible glossary

The result? A bilingual French-Kabiyè glossary structured around four sections for each term:

- The French term, its definition, and its grammatical category.

- The Kabiyè equivalent, carefully transcribed.

- Possible variants depending on the locality.

- An example sentence in Kabiyè, with its translation into French to provide context.

But this glossary is not limited to the written word. It includes audio files containing the pronunciations of terms in French and Kabiyè, to facilitate oral transmission, which is essential in areas where writing remains secondary. A digital version is available on the Minodu project’s collaborative platform. This version includes a simplified transcription of the pronunciation for those who are unable to listen to the audio files and cannot read Kabiyè. The transcript is also available in printed form in a recording booth at Kara University, where students make audio recordings in the

Kabiyè language as part of the Minodu project. Most importantly, the different formats for writing, listening, and context allow everyone to access the glossary.

A tool for land management

This glossary is much more than a lexicon. It is part of a broader strategy: to enable students at the University of Kara to better communicate their research, facilitate data collection in the local language, and make the results accessible to communities. With this in mind, an “audio library” is being built as part of the project, with scientific results transformed into simple and understandable audio in the Kabiyè language.

This approach is an essential building block for creating community-based climate monitoring systems, where residents can take ownership of meteorological information, co-produce relevant knowledge, and better anticipate the effects of climate change on their crops.

A multilingual and multiversal dynamic

Through this meticulous linguistic work, the Minodu project demonstrates that sustainable land management cannot be achieved without serious consideration of local languages and vernacular knowledge. Translating, in this case, means recognizing, connecting, and co-constructing a common language to face climate challenges together.

This process is ongoing: the glossary is still in its early stages. It is designed to be an evolving tool, enriched by feedback from the field, usage, and criticism. It is a space where Kabiyè and climatology continue to dialogue for better results in the field.

Morgan Clarke, a linguistics student and member of the Minodu team, has created an online course to encourage others to take steps towards co-constructing linguistic methods to address climate challenges. It is available on a platform at the University of Kara, and on the Interfaces e-learning platform here: https://share.articulate.com/6ACsRqQFtRn02T8kijhS2 (password: minodu).